Andrew Carnegie. The history of the richest man in the world

Andrew Carnegie

One of the captains of industry of 19th century America, Andrew Carnegie helped build the formidable American steel industry, a process that turned a poor young man into one of the richest entrepreneurs of his age. Later in his life, Carnegie sold his steel business and systematically gave his collected fortune away to cultural, educational and scientific institutions for “the improvement of mankind.”

Carnegie was born in Dunfermline, the medieval capital of Scotland, in 1835. The town was a center of the linen industry, and Andrew’s father was a weaver, a profession the young Carnegie was expected to follow. But the industrial revolution that would later make Carnegie the richest man in the world, destroyed the weavers’ craft. When the steam-powered looms came to Dunfermline in 1847 hundreds of hand loom weavers became expendable. Andrew’s mother went to work to support the family, opening a small grocery shop and mending shoes.

“I began to learn what poverty meant,” Andrew would later write. “It was burnt into my heart then that my father had to beg for work. And then and there came the resolve that I would cure that when I got to be a man.”

An ambition for riches would mark Carnegie’s path in life. However, a belief in political egalitarianism was another ambition he inherited from his family. Andrew’s father, his grandfather Tom Morrison and his uncle Tom Jr. were all Scottish radicals who fought to do away with inherited privilege and to bring about the rights of common workers.

But Andrew’s mother, fearing for the survival of her family, pushed the family to leave the poverty of Scotland for the possibilities in America. She borrowed 20 pounds she needed to pay the fare for the Atlantic passage and in 1848 the Carnegies joined two of Margaret’s sisters in Pittsburgh, then a sooty city that was the iron-manufacturing center of the country.

William Carnegie secured work in a cotton factory and his son Andrew took work in the same building as a bobbin boy for $1.20 a week. Later, Carnegie worked as a messenger boy in the city’s telegraph office. He did each job to the best of his ability and seized every opportunity to take on new responsibilities. For example, he memorized Pittsburgh’s street lay-out as well as the important names and addresses of those he delivered to.

Carnegie often was asked to deliver messages to the theater. He arranged to make these deliveries at night–and stayed on to watch plays by Shakespeare and other great playwrights. In what would be a life-long pursuit of knowledge, Carnegie also took advantage of a small library that a local benefactor made available to working boys.

One of the men Carnegie met at the telegraph office was Thomas A. Scott, then beginning his impressive career at Pennsylvania Railroad. Scott was taken by the young worker and referred to him as “my boy Andy,” hiring him as his private secretary and personal telegrapher at $35 a month.

“I couldn’t imagine,” Carnegie said many years later. “what I could ever do with so much money.” Ever eager to take on new responsibilities, Carnegie worked his way up the ladder in Pennsylvania Railroad and succeeded Scott as superintendent of the Pittsburgh Division. At the outbreak of the Civil War, Scott was hired to supervise military transportation for the North and Carnegie worked as his right hand man.

The Civil War fueled the iron industry, and by the time the war was over, Carnegie saw the potential in the field and resigned from Pennsylvania Railroad. It was one of many bold moves that would typify Carnegie’s life in industry and earn him his fortune. He then turned his attention to the Keystone Bridge Company, which worked to replace wooden bridges with stronger iron ones. In three years he had an annual income of $50,000.

However, Andrew expressed his uneasiness with the businessman’s life. In a letter to himself at age 33, he wrote: “To continue much longer overwhelmed by business cares and with most of my thoughts wholly upon the way to make more money in the shortest time, must degrade me beyond hope of permanent recovery. I will resign business at thirty-five, but during the ensuing two years I wish to spend the afternoons in receiving instruction and in reading systematically.”

Carnegie would continue making unparalleled amounts of money for the next 30 years. Two years after he wrote that letter Carnegie would embrace a new steel refining process being used by Englishman Henry Bessemer to convert huge batches of iron into steel, which was much more flexible than brittle iron. Carnegie threw his own money into the process and even borrowed heavily to build a new steel plant near Pittsburgh. Carnegie was ruthless in keeping down costs and managed by the motto “watch costs and the profits take care of themselves.”

“I think Carnegie’s genius was first of all, an ability to foresee how things were going to change,” says historian John Ingram. “Once he saw that something was of potential benefit to him, he was willing to invest enormously in it.”

Carnegie was unusual among the industrial captains of his day because he preached for the rights of laborers to unionize and to protect their jobs. However, Carnegie’s actions did not always match his rhetoric. Carnegie’s steel workers were often pushed to long hours and low wages. In the Homestead Strike of 1892, Carnegie threw his support behind plant manager Henry Frick, who locked out workers and hired Pinkerton thugs to intimidate strikers. Many were killed in the conflict, and it was an episode that would forever hurt Carnegie’s reputation and haunt the man.

Still, Carnegie’s steel juggernaut was unstoppable, and by 1900 Carnegie Steel produced more of the metal than all of Great Britain. That was also the year that financier J. P. Morgan mounted a major challenge to Carnegie’s steel empire. While Carnegie believed he could beat Morgan in a battle lasting five, 10 or 15 years, the fight did not appeal to the 64-year old man eager to spend more time with his wife Louise, whom he had married in 1886, and their daughter, Margaret.

Carnegie wrote the asking price for his steel business on a piece of paper and had one of his managers deliver the offer to Morgan. Morgan accepted without hesitation, buying the company for $480 million. “Congratulations, Mr. Carnegie,” Morgan said to Carnegie when they finalized the deal. “you are now the richest man in the world.”

Fond of saying that “the man who dies rich dies disgraced,” Carnegie then turned his attention to giving away his fortune. He abhorred charity, and instead put his money to use helping others help themselves. That was the reason he spent much of his collected fortune on establishing over 2,500 public libraries as well as supporting institutions of higher learning. By the time Carnegie’s life was over, he gave away 350 million dollars.

Carnegie also was one of the first to call for a “league of nations” and he built a “a palace of peace” that would later evolve into the World Court. His hopes for a civilized world of peace were destroyed, though, with the onset of World War I in 1914. Louise said that with these hostilities her husband’s “heart was broken.” Carnegie lived for another five years, but the last entry in his autobiography was the day World War I began.

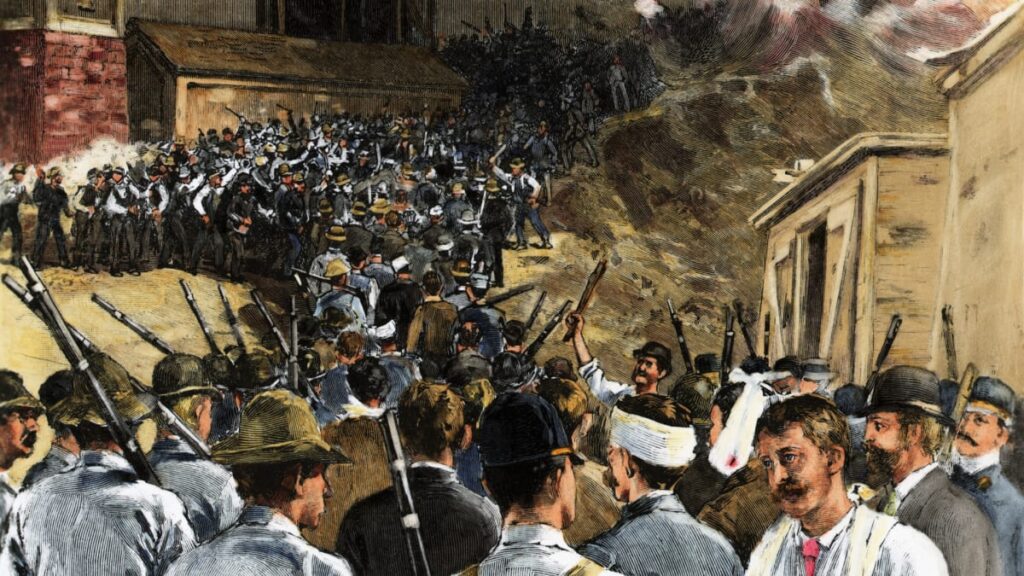

The Homestead Strike

One of the most difficult episodes Andrew Carnegie’s life — and one that revealed the steel magnate’s conflicting beliefs regarding the rights of labor — was the bitter conflict in 1892 at his steel plant in Homestead, Pennsylvania. Carnegie’s involvement in the union-breaking action left many men dead or wounded and forever tarnished Carnegie’s reputation as a benevolent employer and a champion of labor.

The conflict at Homestead arose at a time when the fast-changing American economy had stumbled and conflicts between labor and management had flared up all over the country. In 1892, labor declared a general strike in New Orleans. Coal miners struck in Tennessee, as did railroad switchmen in Buffalo, New York and copper miners in Idaho.

Carnegie’s mighty steel industry was not immune to the downturn. In 1890, the price of rolled-steel products started to decline, dropping from $35 a gross ton to $22 early in 1892. In the face of depressed steel prices, Henry C. Frick, general manager of the Homestead plant that Carnegie largely owned, was determined to cut wages and break the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers, one of the strongest craft unions in the country.

Behind the scenes, Carnegie supported Frick’s plans. In the spring of 1892, Carnegie had Frick produce as much armor plate as possible before the union’s contract expired at the end of June. If the union failed to accept Frick’s terms, Carnegie instructed him to shut down the plant and wait until the workers buckled. “We… approve of anything you do,” Carnegie wrote from England in words he would later come to regret. “We are with you to the end.”

With Carnegie’s carte blanche support, Frick moved to slash wages. Plant workers responded by hanging Frick in effigy. At the end of June, Frick began closing down his open hearth and armor-plate mills, locking out 1,100 men. On June 25th, Frick announced he would no longer negotiate with the union; now he would only deal with workers individually. Leaders of Amalgamated were willing to concede on almost every level — except on the dissolution of their union. Workers tried to reach the Carnegie who had strongly defended labor’s right to unionize. He had departed on his annual and lengthy vacation, traveling to a remote Scottish castle on Loch Rannoch. He proved inaccessible to all — including the press and to Homestead’s workers — except for Frick.

“This is your chance to re-organize the whole affair,” Carnegie wrote his manager. “Far too many men required by Amalgamated rules.” Carnegie believed workers would agree to relinquish their union to hold on to their jobs.

It was a severe miscalculation. Although only 750 of the 3,800 workers at Homestead belonged to the union, 3,000 of them met and voted overwhelmingly to strike. Frick responded by building a fence three miles long and 12 feet high around the steelworks plant, adding peepholes for rifles and topping it with barbed wire. Workers named the fence “Fort Frick.”

Deputy sheriffs were sworn in to guard the property, but the workers ordered them out of town. Workers then took to guarding the plant that Frick had closed to keep them out. This action signified a very different attitude that labor and management shared toward the plant.

“Workers believed because they had worked in the mill, they had mixed their labor with the property in the mill,” explains historian Paul Krause. “They believed that in some way the property had become theirs. Not that it wasn’t Andrew Carnegie’s, not that they were the sole proprietors of the mill, but that they had an entitlement in the mill. And I think in a fundamental way the conflict at Homestead in 1892 was about these two conflicting views of property.”

Frick turned to the enforcers he had employed previously: the Pinkerton Detective Agency’s private army, often used by industrialists of the era. At midnight on July 5, tugboats pulled barges carrying hundreds of Pinkerton detectives armed with Winchester rifles up the Monongahela River. But workers stationed along the river spotted the private army. A Pittsburgh journalist wrote that at about 3 A.M. a “horseman riding at breakneck speed dashed into the streets of Homestead giving the alarm as he sped along.” Thousands of strikers and their sympathizers rose from their sleep and went down to the riverbank in Homestead.

When the private armies of business arrived, the crowd warned the Pinkertons not to step off the barge. But they did. No one knows which side shot first, but under a barrage of fire, the Pinkertons retreated back to their barges. For 14 hours, gunfire was exchanged. Strikers rolled a flaming freight train car at the barges. They tossed dynamite to sink the boats and pumped oil into the river and tried to set it on fire. By the time the Pinkertons surrendered in the afternoon three detectives and nine workers were dead or dying. The workers declared victory in the bloody battle, but it was a short-lived celebration.

The governor of Pennsylvania ordered state militia into Homestead. Armed with the latest in rifles and Gatling guns, they took over the plant. Strikebreakers who arrived on locked trains, often unaware of their destination or the presence of a strike, took over the steel mills. Four months after the strike was declared, the men’s resources were gone and they returned to work. Authorities charged the strike leaders with murder and 160 other strikers with lesser crimes. The workers’ entire Strike Committee also was arrested for treason. However, sympathetic juries would convict none of the men.

All the strikers leaders were blacklisted. The Carnegie Company successfully swept unions out of Homestead and reduced it to a negligible factor in the steel mills throughout the Pittsburgh area.

Carnegie found the upheaval and its aftermath a devastating experience. When British statesman William E. Gladstone wrote him a sympathetic note, Carnegie replied:

This is the trial of my life (death’s hand excepted). Such a foolish step — contrary to my ideals, repugnant to every feeling of my nature. Our firm offered all it could offer, even generous terms. Our other men had gratefully accepted them. They went as far as I could have wished, but the false step was made in trying to run the Homestead Works with new men. It is a test to which workingmen should not be subjected. It is expecting too much of poor men to stand by and see their work taken by others. . . The pain I suffer increases daily. The Works are not worth one drop of human blood. I wish they had sunk.

Carnegie would come back to Homestead six years later to dedicate a building that would house a library, a concert hall, a swimming pool, bowling alleys, and a gymnasium. However, the man who saw himself as a progressive businessman would always carry pain regarding the incident. “Nothing. . . in all my life, before or since, wounded me so deeply,” he wrote in his autobiography. “No pangs remain of any wound received in my business career save that of Homestead.”

“It’s easy to say that Carnegie was a hypocrite,” states historian Joseph Frazier Wall. “And there is an element of hypocrisy clearly in between what he said and what was done. But it’s a little too easy to simply dismiss the whole incident on Carnegie’s part as an act of hypocrisy. There is this curious reason as to why Carnegie felt it necessary to even enunciate the rights of labor. Frick was the norm, not Carnegie, in management’s relationship with labor at that time. And, one can only answer that, once again, it’s being torn between wanting to pose as a great democrat and liberal and at the same time wanting to make sure Carnegie Steel came out on top.”

Carnivals of Revenge

The frustrations of Gilded Age workers transformed the labor movement into a vigorous, if often violent, force. Workers saw men like Andrew Carnegie getting fabulously rich, and raged at being left behind. With their own labor the only available bargaining chip, workers frequently went on strike. The 1880’s witnessed almost ten thousand strikes and lockouts; close to 700,000 workers struck in 1886 alone.

The results were often explosive-none more than the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. When the B&O; Railroad cut wages, workers staged spontaneous strikes, which spread nationwide. In Baltimore, the state militia fired on strikers, leaving 11 dead and 40 wounded. In Pittsburgh, Andrew Carnegie’s mentor, Thomas Scott of the Pennsylvania Railroad, urged that strikers be given “a rifle diet for a few days and see how they like that kind of bread.” In Philadelphia, strikers battled local militia, burning much of the downtown area before the federal troops intervened. The wage reductions remained in place, and the War Department created the national guard to put down future disturbances.

Industrialists took a harder line against unions, but the labor movement grew. In 1877, three national unions existed; in 1880 there were eighteen. For many Americans, unionization fed a fear that “barbarians” had invaded the nation. During a Cleveland steel strike, violent confrontations led local newspapers to attack the “un-American” Polish workers as “Ignorant and degraded whelps,” “Foreign devils,” and “Communistic scoundrels [who] revel in robberies, bloodshed, and arson.”

In 1886, a national strike called for changing the standard workday from 12-hours to eight. At 12,000 companies nationwide, 340,000 workers stopped work. In Chicago police were trying to break up a large labor meeting in Haymarket Square, when a bomb exploded without warning, killing a police officer. Police fired into the crowd, killing one and wounding many more. As a result of the riot, four labor organizers were hanged.

The hangings demoralized the national labor movement and energized management. By 1890, Knights of Labor membership had plummeted by ninety percent. The 1892 battle at Carnegie’s Homestead mill became a model for stamping out strikes: hold firm and call in government troops for support.

The brutal depression of 1893-94 triggered some of the worst labor conflicts in the country’s history, including the strike against the Pullman Palace Car Company. When George Pullman slashed wages and hiked rents in his company town, a national strike and boycott was called on all railways carrying Pullman cars. Railroad traffic ground to a halt as 260,000 workers struck, and battles with state and federal troops broke out in 26 states. The strike ultimately failed, its leaders imprisoned and many strikers blacklisted.

The labor movement lay in shambles, and would not rise again for nearly fifty years. Although workers would find new strength in the next century, they would never again pose the same broad challenge to the claims of capital.

Strike at Homestead Mill: The Hated Men in Blue

Homestead mayor “Honest” John McLuckie, like all labor leaders, despised the Pinkertons: “Our people as a general thing think they are a horde of cut-throats, thieves, and murderers and are in the employ of unscrupulous capital for the oppression of honest labor.” Hated by laborers nationwide, the Pinkertons had long been used to bust strikes-often by busting heads.

In the late nineteenth century, labor disputes often erupted into violent riots, and a cottage industry sprang up to serve the paramilitary needs of the modern industrialist. Local sheriffs were usually too poorly equipped or too sympathetic to labor to put down strikes. The Pinkerton Detective Agency, on the other hand, staked its reputation on crushing labor actions. Between 1866 and 1892, Pinkertons participated in seventy labor disputes and opposed over 125,000 strikers.

Even before the Homestead strike, Carnegie and Frick had employed the Pinkertons. Frick used the agency twice in his coal fields: in 1884 to protect Hungarians and Slavs whom he had brought in as strikebreakers; and in 1891 to protect Italian strikebreakers, brought in against the then-striking Hungarians and Slavs. Carnegie used Pinkertons to protect strike breakers in 1887 and hired them twice in 1889 when strikes seemed imminent, facts he later conveniently forgot.

The Pinkerton Detective Agency was founded in 1850 by a young Scottish immigrant, Allan Pinkerton. Curiously, Pinkerton had been a Chartist in Scotland like Carnegie’s father, agitating for the rights of the British working class. His detectives gained national attention by fighting the “Molly Maguires,” a secret society of Irish coal miners credited with massive violence against coal companies in eastern Pennsylvania. Pinkertons infiltrated the organization and had many of the Mollies arrested and some hanged.

Critics alleged that the Pinkertons had planted evidence during their investigation of the Mollies and had thrown the bomb that sparked Chicago’s Haymarket Riot of 1886 in order to discredit unions. Whether or not these rumors were true, it was certainly the case that Pinkerton agents were not above stirring up a little trouble where it did not previously exist-just to drum up business.

In most cases, however, the Pinkertons’ conduct was strictly within the law, if not entirely popular. If strikers threatened a company’s property rights, that company was expected to strike back, even violently, in order to restore “law and order.” Ironically, the detectives, like most workers, were immigrants working for a wage; when the workers at Homestead fought the Pinkertons, they were really fighting themselves. “The person who employed that force,” said Mayor McLuckie, “was safely placed away by the money that he has wrung from the sweat of the men employed in that mill.”

Gilded Age

“What is the chief end of man?–to get rich. In what way?–dishonestly if we can; honestly if we must.”

— Mark Twain-1871

During the “Gilded Age,” every man was a potential Andrew Carnegie, and Americans who achieved wealth celebrated it as never before. In New York, the opera, the theatre, and lavish parties consumed the ruling class’ leisure hours. Sherry’s Restaurant hosted formal horseback dinners for the New York Riding Club. Mrs. Stuyvesant Fish once threw a dinner party to honor her dog who arrived sporting a $15,000 diamond collar.

While the rich wore diamonds, many wore rags. In 1890, 11 million of the nation’s 12 million families earned less than $1200 per year; of this group, the average annual income was $380, well below the poverty line. Rural Americans and new immigrants crowded into urban areas. Tenements spread across city landscapes, teeming with crime and filth. Americans had sewing machines, phonographs, skyscrapers, and even electric lights, yet most people labored in the shadow of poverty.

To those who worked in Carnegie’s mills and in the nation’s factories and sweatshops, the lives of the millionaires seemed immodest indeed. An economist in 1879 noted “a widespread feeling of unrest and brooding revolution.” Violent strikes and riots wracked the nation through the turn of the century. The middle class whispered fearfully of “carnivals of revenge.”

For immediate relief, the urban poor often turned to political machines. During the first years of the Gilded Age, Boss Tweed’s Tammany Hall provided more services to the poor than any city government before it, although far more money went into Tweed’s own pocket. Corruption extended to the highest levels of government. During Ulysses S. Grant’s presidency, the president and his cabinet were implicated in the Credit Mobilier, the Gold Conspiracy, the Whiskey Ring, and the notorious Salary Grab.

Europeans were aghast. America may have had money and factories, they felt, but it lacked sophistication. When French prime minister Georges Clemenceau visited, he said the nation had gone from a stage of barbarism to one of decadence — without achieving any civilization between the two.

Margaret Carnegie

Many influences carved Carnegie’s personality, including his Scottish roots, his family’s struggle with poverty, the egalitarian spirit of his extended family, and even the city of Pittsburgh, one of centers of 19th century industrial America. Many people, from industrialists to philosophers, also shaped Carnegie the man. Yet the most influential of all was most likely his mother Margaret, the backbone of his family, who resided with Carnegie until her death when Carnegie was still a 51-year old bachelor.

Carnegie was the first to acknowledge the role his mother played. “Perhaps some day I may be able to tell the world something of this heroine, but I doubt it,” Carnegie wrote in his autobiography. “I feel her to be sacred to myself and not for others to know. None could ever really know her–I alone did that. After my father’s early death she was all my own.”

Andrew, her first son, was born in Scotland in 1835 to the 25-year old Margaret. By the mid-1840’s, the family was sliding into abject poverty. William, Margaret’s husband, was a hand weaver who was losing his trade to the new power-driven factory looms. The family had to leave their large house and move back to small quarters. Margaret opened a small food store to add to the family’s income. As of the winter of 1847-1848, it was not at all clear that the family would survive Scotland’s industrialization.

Carnegie’s mother taught the young Carnegie the frugality that he would become famous for later. One day in school he quoted a proverb that his mother had repeated often: “Look after the pennies and the pounds will look after themselves.” His classmates laughed at him, unaware that the principle would help make Carnegie one of the richest men in the world.

Many of Margaret’s countrymen fled to the promise of America, including two of Margaret’s sisters and a brother who had emigrated to Pennsylvania and Ohio. One of her sisters wrote home to Margaret to tell her of the better life that awaited her across the ocean:

This country is far better for the workingman than the old one, and there is room enough to spare, notwithstanding the thousands that flock into her borders every year. As for myself, I like it much better than at home, for in fact you seem to breathe a freer atmosphere here; but as my husband says, no wonder women like it, for they are so much thought of in this country.

Margaret followed her two sisters to Pittsburgh. Her husband took up the grueling factory work at a nearby cotton mill, but he soon left it to return to his handloom to make tablecloths that he sold door to door. Mrs. Carnegie, once again picking up the financial slack, took up sewing shoes for a shoemaker in the neighborhood. During the time his family was still poor, Andrew found his mother crying about the family’s struggles.

“Some day,” Andrew promised, “I’ll be rich, and we’ll ride in a fine coach driven by four horses.” Margaret was quick to reply: “That will do no good over here, if no one in Dunfermline can see us.” It was then that Carnegie resolved that he would one day revisit Dunfermline with his mother in a coach that the entire town would notice.

Even before Margaret’s husband died in 1855, the family tied its financial star to Andrew, who supported his mother and his younger brother Tom. In 1859, Andrew was appointed superintendent of the Western Division of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company. His salary was raised to $125 a month, which put his family into a comfortable position. Andrew moved with his mother and 16-year old brother, Tom to the East Liberty neighborhood of downtown Pittsburgh, a fashionable area.

In 1867, Andrew and his mother moved to New York City, his brother Tom having started a family of his own. After a few years at the St. Nicholas Hotel, the two moved uptown to the Windsor Hotel on Fifth Avenue, then a more residential neighborhood that suited his mother. Often away for trips, Carnegie knew his mother could be cared for by hotel staff, a luxury that the matriarch in the family enjoyed fully. Andrew sometimes expressed a desire to have his own dining room to entertain guests, but Mrs. Carnegie liked where she lived, once responding, “We cannot do better than this.”

Andrew’s mother not only rode his coattails; she also was possessive of her son. In 1880, when Margaret was approaching 70 and her son was already 45, that a serious threat was made to her dominion. Andrew became friendly with an intelligent woman named Louise Whitfield, a daughter to one of his business associates and 21 years Carnegie’s junior. The two got to know each other while horseback riding through Central Park and over time they became more than friends.

In 1881, Carnegie now a very rich man, decided to follow through on his promise to take his mother back to Dunfermline in style, and he wanted to take Louise as well. Andrew asked his mother to convince Louise’s family that the trip would be appropriate for a young, single lady. Mrs. Carnegie went to visit Louise and her mother, but her intention appears to have been to subvert Louise’s voyage. When Mrs. Whitfield asked the elderly Mrs. Carnegie whether such a trip was appropriate for a young unattached woman, Andrew’s mother answered with conviction: “If she were a daughter of mine she wouldna’ go.” Louise, dejected, stayed behind.

Mother and son, accompanied by friends, returned now to the home the Carnegie family had abandoned 33 years ago. This time they went back as rich benefactors, as Carnegie had bequeathed a new library to his first home. Thousands of townspeople greeted them with frenzied cheers, hanging banners such as “Welcome Carnegie, Generous Son.” The Carnegies had left Dunfermline in steerage, but they came back to town in a magnificent coach, as Carnegie had promised his mother. As Margaret rode through the town in her carriage, she cried tears of joy. It may very well have been Margaret’s crowning hour, a final triumph for the woman who as a young mother left her home fearing destitution.

Despite the snub, the romance between Louise and Andrew continued. In September, 1883, the two were secretly engaged. Yet when it came to setting a date for the wedding, Carnegie balked. The two agreed to call off the engagement.

Only after Margaret’s death in November, 1886, could Carnegie commit to marrying Louise. Carnegie, recuperating from typhoid fever, wrote her soon after he lost his mother: “It was six weeks since the last word was written and that was to you as I was passing into the darkness. Today as I see the great light once more my first word is to you. . . Louise, I am wholly yours–all gone but you. . . I live in you now. Write me. I only read yours of six weeks ago today. Till death, Louise, yours alone.”

The two married and had a daughter, who they named Margaret. After Andrew died, Louise confided to one of Carnegie’s biographers that her mother-in-law was the most unpleasant person she had ever known, an assessment the adoring son Andrew would certainly have disputed.

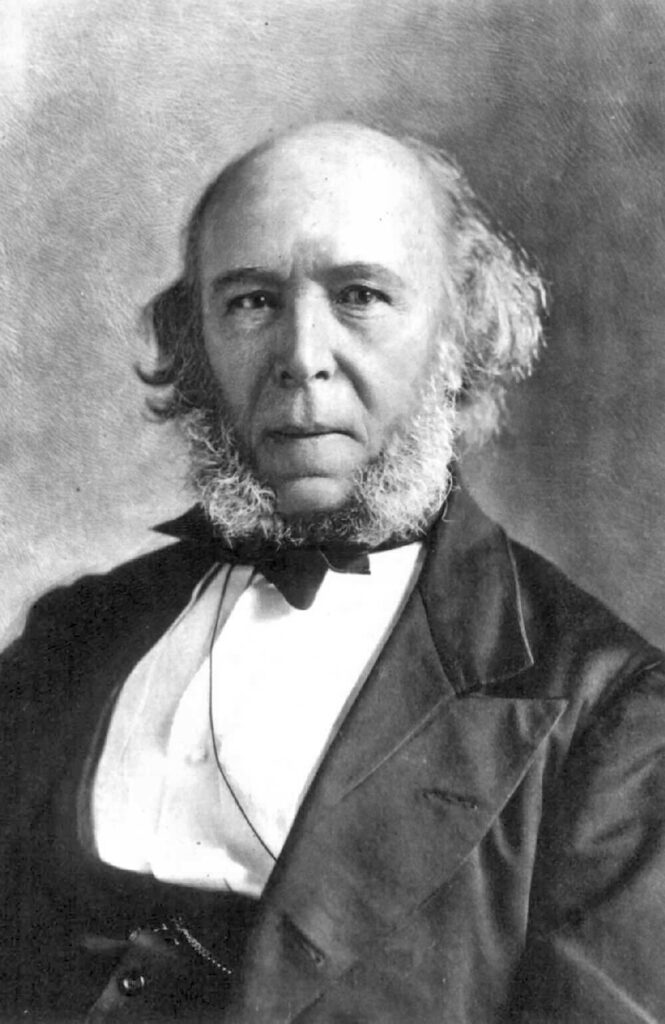

Herbert Spencer

Andrew Carnegie, already a titan of the business world, was sitting with friends on the moors of Scotland when the group took up the question of which author they would take with them if stranded on a deserted island. One said Shakespeare, another chose Dante. Carnegie didn’t hesitate. “Herbert Spencer,” he said.

Of all the writers that Carnegie read and studied throughout his life, he said that the English philosopher Herbert Spencer was the one who influenced him most. Spencer’s writings provided the philosophical justification for Carnegie’s unabashed pursuit of personal riches in the world of business, freeing him from the moral reservations about financial acquisition that he had inherited from his egalitarian Scottish relatives.

In his “Autobiography,” Carnegie wrote about the dramatic effect of reading both the naturalist Charles Darwin and Spencer.

“I remember that light came as in a flood and all was clear,” Carnegie wrote. “Not only had I got rid of theology and the supernatural, but I had found the truth of evolution. ‘All is well since all grows better’ became my motto, my true source of comfort.”

Spencer adapted Charles Darwin’s notion of natural selection and applied the theory to human society in a philosophy that became known as “Social Darwinism.” It was Spencer who coined the term “survival of the fittest,” using it to apply to the fate of rich and poor in a laissez faire capitalist society. Spencer argued that there was nothing unnatural — and therefore wrong — with competing and then rising to the top in a cut- throat capitalist world.

“Spencer told [Carnegie] that it was a scientific fact that somebody like him should be getting to the top,” says historian Owen Dudley Edwards. “That there was nothing unnatural about it, wrong about it, evil about it.”

Not only was competition in harmony with nature, Spencer believed, but it was also in the interest of the general welfare and progress of society. Many successful capitalists of the late 19th century embraced Spencer’s philosophy. These captains of industry used his words as justification to oppose social reform and government intervention. As Spencer said, these would interfere with the natural — and beneficial — law of survival.

“The concentration of capital is a necessity for meeting the demands of our day, and as such should not be looked at askance, but be encouraged,” Carnegie wrote, paraphrasing Spencer. “There is nothing detrimental to human society in it, but much that is, or is bound soon to become, beneficial.”

Yet Carnegie did not follow all of Spencer’s teachings, especially Spencer’s call for unfettered laissez faire capitalism. Carnegie argued, for example, that if workers were to have an eight-hour day, the state would have to regulate it — something that Spencer never would have approved. Carnegie also ignored Spencer’s complete opposition to philanthropy, as the American business tycoon was one of the great philanthropists of his day. Spencer held that the poor were the unfit who would not survive; Carnegie, however, believed that the poor (such as himself) were often the ones who grew up to become “the epoch-makers.”

Carnegie not only admired Spencer; he also sought out his friendship. Carnegie was in England at the time he learned of Spencer’s scheduled tour of America, where the Englishman’s popularity was greatest. The steel magnate made hurried plans to return to the States on the same ship as Spencer and even managed to win a place at the same dining table with Spencer.

For nine days Carnegie used his ample charms to win over the difficult philosopher. Both Carnegie and Spencer recalled in their autobiographies an incident that revealed Carnegie’s fearlessness and social confidence. The two men were sitting at a table of diners who were discussing whether great men lived up to their reputations when met in person. Carnegie argued that reality never lived up to expectations. In his autobiography, the steel tycoon described what happened next:

“Oh!’ said Mr. Spencer, “in my case, for instance was this so?”

“Yes,” I replied, “You more than any. I had imagined my teacher, the great calm philosopher brooding Buddha-like, over all things, unmoved; never did I dream of seeing him excited over the question of cheshire or Cheddar cheese.” The day before he [Spencer] had peevishly pushed away the former when presented by the steward exclaiming “Cheddar, Cheddar, not Cheshire; I said Cheddar.” There was a roar in which none joined more heartily than the sage.

During the voyage, Carnegie used all his powers to convince Spencer to include Pittsburgh on his itinerary. The business tycoon argued that the Edgar Thomson Bessemer steel plant was evidence of the industrial order that Spencer had declared as the next and final stage of man’s social evolution. Spencer finally agreed to the stop, and when he arrived in Pittsburgh, Carnegie and his partners met him at the station.

Spencer, however, was not as impressed with Pittsburgh as was Carnegie. The visitor complained about the smoky, polluted air. The heat and noise of the mills almost forced the sickly Spencer to collapse at one point. When the tour was over and Spencer was about to leave, he gave his verdict of Pittsburgh, one that must have hurt the city’s champion: “Six months residence here would justify suicide.”

Carnegie was also hurt by Spencer’s attraction to Andrew’s younger brother Tom. Tom’s natural shyness seemed to appeal to Spencer more than Andrew’s desire to please and impress. Tom had also read Spencer’s works, and his questions impressed the philosopher so much that Spencer invited Tom to accompany him to Washington and New York, although Andrew’s younger brother declined.

At the end of the American tour, Carnegie picked up Spencer on the day he was honored at a farewell dinner at Delmonico’s in New York City. Carnegie saw that the great man was worried about the evening. Wrote Carnegie: “He could think of nothing but the address he was to deliver. I believe he had rarely before spoken in public.” Some of the most important businessmen of the day made toasts to the philosopher. Interestingly enough, when it was Spencer’s turn to speak, he did not encourage the gathered to continue to wage the competitive battle. Instead, Spencer, exhausted by his visit (Spencer was a fragile man and a hypochondriac), suggested that Americans learn how to find time to enjoy their leisure.

Many who had contact with Spencer judged his trip a failure, since Spencer spent much of his time complaining about hosts and avoiding the press. Yet the visit was salvaged in Carnegie’s mind while the men were on deck of the ship that would take Spencer back across the Atlantic. Spencer, in a gesture uncommon to him, held the hands of Carnegie and editor Edward Youmans and said, “Here are my two best American friends.” It was a gesture that Carnegie would recall often and obviously cherish.